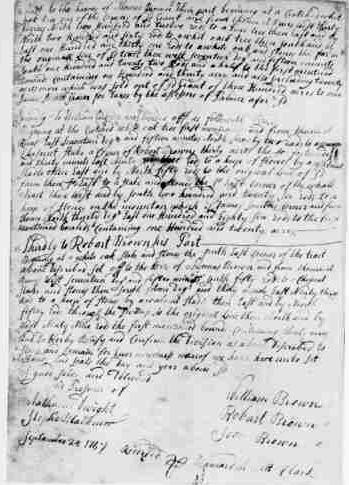

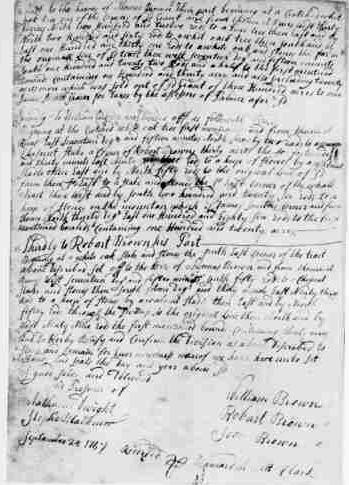

Real estate transaction entered by Barnard McNitt

in Palmer town record

Standing behind the old house is a great elm that a tree expert has declared to date from the year 1650 or thereabouts. When Barnard was erecting his bam and perhaps his first new house, the elm was about eighty-five years old. The trunk now has a girth of sixteen and a half feet, and the branches have a spread of 112 feet. Each of the five branches is about seven and a half feet in circumference.

Barnard financed his building operations by borrowing L40 from Alexander Ewing of Ashford, Windham County, Connecticut. As security he pledged his second drawing of 100 acres of land to which he was entitled by virtue of the confirmation given his title of ownership by the General Court in 1733. The additional land, adjoining his original farm, was not actually granted to him until May 16, 1746. Ewing accepted from Barnard a deed to the anticipated grant of 100 acres, dated May 12, 1735; it is evident the loan was repaid long before the land came into Barnard's possession.

The vital records of Palmer supply information of births and marriages of Barnard's children, beginning with 1729, but there is a gap for the period before the family came to the neighborhood. That the eldest son Alexander was born in 1721 is established by the inscription on his gravestone at Salem, New York. [SEE NOTE 1] The record of the birth of Elisabeth in 1729 indicates the family was at Palmer then, three years before the purchase of the farm in 1732.

Since the names of Joseph and Arthur do not appear in Palmer records of baptisms, it must seem they were born before 1729, and elsewhere, or that they may have been nephews, adopted into the family. The fact of their recorded marriages to Palmer girls in 1761 and 1765 warrants including them in the roll of children. [SEE NOTE 2]

Barnard evidently was married in 1720 just before taking ship to the

(end of page 32)

Massachusetts Bay Colony. As in so many other cases threatening lifelong separation from those left behind, he may have proposed to his favorite girl that she marry him right away and cross the sea with him. It has been recorded in the family of his son John that Barnard was born in 1700, which may be an approximation. Early marriages were not at all unusual then. And since a period of thirty-three years elapsed between the birth of his son Alexander in 1721 and of his daughter Jean in 1754, it must be concluded Barnard was twice marred. Jean is the only wife to whom the Palmer records refer, and she must have come there with him, hardly more than a young girl when Elisabeth was born in 1729. [SEE NOTE 3]

Here then is the record of Barnard's family; we may consider the three eldest the sons of a first wife, and the others as Jean's children:

| [SEE NOTE 4] |

|

|

|

| 1. Alexander | 1721 | Elisabeth McClem, at Pelham | April 14 1749 |

| 2. Joseph | ? | Elisabeth Ward | Nov. 7, 1761 |

| 3. Arthur | ? | Jane Quinton | Sept. 4, 1765 |

| 4. Elisabeth | March 28, 1729 | --------------- | |

| 5. David | April 27, 1731 | Martha Patrick, at Rutland | March 18, 1756 |

| 6. William | July 25, 1733 | Elisabeth Thomson | May 8, 1755 |

| 7. Sarah | May 29, 1737 | Isaac Farrell | Aug. 27, 1762 |

| 8. James | Jan. 1, 1739 | Name of wife, place of marriage undiscovered | |

| 9. Mary | May 6, 1744 | Josiah Farrell | April 9, 1768 |

| 10. Adam | May 6, 1744 | --------------- | |

| 11. Margaret | Dec. 15, 1746 | Reuben Cooley | Jan. 22, 1772 |

| 12. John | April 25, 1749 | 1st, Mary Fuller; 2nd, Patty Wilson at Murrayfield | Dec. 23, 1773

Jan. 14, 1777 |

| 13. Andrew | Aug. 15, 1750 | Chloe Chapin | July 18, 1771 |

| 14. Jean | Aug. 25, 1754 | Thomas Brown | Dec. 15, 1774 |

The Elbows community was first designated as a plantation, then as a district; not until the onset of the Revolution was it permitted the dignity of a township form of government. Meetings of "Proprietors and Grantees" were held from the beginning, and Barnard served variously as member of the auditing committee, clerk, and moderator.

He was clerk of the plantation from 1741 to 1750, and after the district of Palmer was authorized by the General Court, he was clerk from 175 5 to 1761. He also was a member of the board of selectmen in 1754 and 1755. He was a member of the committee that chose the site and laid out the first cemetery at the Old Center, and was constantly called upon to serve on committees to dispose of matters that in modern times are handled by town officers.

(end of page 33)

The first house beside Wigwam Brook undoubtedly was a log cabin, because only logs were available for building before the sawmills began operating in the neighborhood, in and after 1730. The name of the brook suggests the character of former dwellers in the Indian meadow between the stream and the Cedar mountain range directly at the east.

Many arrowheads and stone axes have been picked up in modern times along the banks of the brook at Barnard's place, and a small collection of them is now kept at the Palmer house.

The English settlers in Massachusetts had small use for an odd item of food introduced by the Ulster Scots: the potato. They regarded it as coarse and harsh-tasting, and were slow to admit it to their tables. Another innovation from Ulster was the small spinning wheel, with the attendant art of weaving fine linen cloth with threads spun from flax. Without doubt Barnard had a small field of flax somewhere near the brook; after cutting the full-grown stalks he would place them in the brook to soak until the fibers were sufficiently separated to permit hackling. The loosened and dried fibers went eventually to the spinning wheel.

Temple says: "The Scotch women - wives and daughters of the early settlers of this town [Palmer] and Pelham - excelled in the art of spinning fine linen thread..... Scotch linen at once became fashionable and in demand among the more wealthy families -- greatly to the advantage of our people at The Elbows." No doubt Jean McNitt and her daughters also spun woolen yarn on the large wheel, and perhaps they had a loom for weaving linsey-woolsey (of linen and wool) for the family clothing.

The principal crops grown by Barnard and other Ulster-Scottish farmers around Palmer, besides potatoes and flax, were Indian corn, summer wheat, rye, peas, oats, and barley. Wheat then was worth five shillings a bushel in cash, or eight shillings in barter. When the minister accepted wheat in part payment of his L80 a year, his account was charged at the barter rate: eight shillings. Rye, barley, and peas were worth four shillings in currency, and corn, three shillings, with proportionately higher prices in barter.

Nearby grain mills with their water wheels, set up alongside the small rivers, ground wheat and corn into flour and meal for home use, and surpluses were carted to Springfield for sale to traders. Carting was an arduous job in those days because the roads were narrow, rough, and without bridges. The streams had to be forded. It was common to fell a large tree across a brook or narrow river and hew the upper surface flat, to provide foot passage for those who walked.

(end of page 34)

Frank McNitt at 37; above library mantel in Palmer house is self-portrait at 21. -- see p. 131 |

Frank's portrait of his wife Virginia, which hangs in Palmer house |

Cattle and hogs were raised numerously for the family larder and for sale. There was no refrigeration then, of course, and at hog-killing time in the autumn, pork was "put down" in barrels of brine for winter fare. Hams were preserved by smoking over smouldering corncobs or hickory in tight little smoke-houses. Ears of corn were hung by their stripped-back husks on beams in kitchen ceilings to dry while waiting their call to usefulness. Chickens roamed yard and field, buying time with their eggs until festival occasions brought them to their appointed end. The Quabaug and Ware Rivers abounded in fish, and the surrounding woods in wild turkeys, quail, partridges, and other game. Trout still may be seen in Wigwam Brook, and deer find shelter in the nearby woods to this day.

Molasses as a spread for bread and for cooking and baking was a staple necessity. The Ulster Scots in New England bartered for it by the gallon and seemed never to have enough in the house to last. Another staple with the men was rum: hot, potent rum distilled in New England from molasses brought from the West Indies in sailing ships. Whenever neighbors gathered to raise the heavy frames of a house or barn, rum was provided in pails. For every husking bee and road-making job, too, as well as for any gathering of neighbors, or a wedding, or a funeral, or perhaps even a meeting of the kirk session, the wine of the New England country was hospitably served. We read little complaint of drunkenness, though.

One egg could be traded at a small neighborhood shop for a glass of rum, and there is a legend of one thrifty soul who demanded a dividend when he brought a double-yolked egg.

An early community leader was Steward Southgate, whose father had brought his family from England in 1715, and had settled in 1718 in Leicester. Harvard graduate and civil engineer, Southgate surveyed the community and laid out farms. He secured confirmation of land titles from the General Court; then was authorized to call the first plantation meeting, held August 7, 1733, at which he served as clerk. He was on the committee chosen to engage the first minister, and on another committee entrusted with L50 to build a meeting house thirty by thirty-six feet in dimensions on a knoll in what came to be called the Old Center. A store, a tavern, and a blacksmith shop were built near the church. The latter disappeared long ago; the others and a few houses remain to mark the first community center.

The Rev. John Harvey, a Presbyterian minister from Ulster who had been preaching in homes and living on voluntary contributions since 1730, was invited by Southgate's committee in 1733 to become the

(end of page 35)

established minister. He was offered L80 a year, the use of the ministry lot of 100 acres in addition to his own farm of the same size, L100 with which to build a house, and all the firewood he needed. Perhaps he was glad to accept.

He was ordained on June 5, 1734 under a white oak tree in a pasture lot east of the Old Center road, about a mile north of Barnard's home. Four Presbyterian ministers and one Congregationalist came from points as distant as Boston and Londonderry to read the Scripture and pray and preach and deliver the charge, no doubt in the company of the entire community. The scene may be recaptured in imagination now as one views the lonely pasture, with the white oak tree that seems never to have attained its growth.

Mr. Harvey continued preaching in homes until November 1735; then the plain little unheated church was ready. The godly felt it their duty to shiver, and try to forget the warmed houses where they had worshiped in preceding winters. In coldest weather, Temple says, the minister led his flock to the nearby tavern and used the bar for a pulpit.

Five plain benches on either side of the center aisle of the church provided the principal seating, with box pews along the side walls for those wishing to pay for their use. The men sat on the benches on one side in the order of their taxpaying rank; their wives sat in corresponding positions across the aisle. In the seating list for 1764, Barnard McNitt appears as the eighth largest taxpayer, entitled to the first seat on the second bench.

Sons and daughters were assigned seats in the gallery. Of the younger generation of the McNitt family, only two were accredited to seats, on the girls' side above their mother. They were Mary, nearing twenty, and Margaret, who was seventeen that year. Jean, the baby of the family, was only ten and perhaps too young for recognition. John and Andrew still were at home, aged fifteen and fourteen, and they were overlooked too. Could they have managed to get out of going to church? It seems hardly possible.

Although Steward Southgate had led in engaging the minister, building the church, and arranging the ordination service under the oak tree in 1734, he was unhappy. A Congregationalist, he was not pleased with the idea of being taxed to support a Presbyterian ministry. Nor can we be much surprised at that, in itself. He found what seemed an excellent opportunity to get rid of the Rev. Mr. Harvey and proceeded to action.

On September 19, 1739, the General Court of Massachusetts received a petition from Southgate and twenty-seven others asking to be relieved of paying taxes to support Mr. Harvey. He had been drinking too much

(end of page 36)

rum, the petition recited; he had been indicted by a Hampshire County grand jury for intemperance on ye first Tuesday of March 1738, and had been convicted on his own confession of guilt, by a justice of the Court of General Sessions in Northampton.

Copies of the record had been given the Presbytery: "Yett nothwithstanding they clearly acquitted him of sd crime against clear and manifest evidence," despite the "authentick record of his own confession." The Presbytery of four ministers had tried Mr. Harvey after his conviction at the county seat, heard his humble confession and promises to do better, and had told him to go freely and sin no more. All this to the great affliction of Steward Southgate and his fellow-petitioners, who included a few of the sterner Scots.

How stood Barnard McNitt? An answering remonstrance was presented to the General Court on December 14, 1739, signed by Barnard and forty-five others: a majority of the congregation. The men who rose to defend the minister bore such Scottish names as Wilson, Blair, Lamont, McElwain, McMaster, Hunter, Rutherford, Shaw, McClenathan, Nevins, Spear, Breckinridge, Little, Thomson, Ferguson, and Sloan.

This petition pointed out that the grievance was "national"; that Southgate and other English Congregationalists were dissatisfied because the ordination of Mr. Harvey had been performed "for the most part by pious and orthodox ministers of another nation." Assimilation had not yet begun, apparently. The American melting pot was not yet working.

"Mr. Southgate and some few others have since that ordination set themselves against the Rev. Mr. Harvey, seeking by all possible means to blast his reputation. . . . As to the Council of Ministers or Presbytery in June last, that would not allow Mr. Southgate's wife and mother and sisters to be sworn of stories nine years old: We produce their [the Presbytery's] definitive sentence, and submit it to the judgment of this Honbl Court, humbly conceiving it must carry in the face of it more weight than all the hard and indecent language of ye petitioners against it; and further declare that Mr. Southgate then consented to it and professed a reconciliation with Mr. Harvey in these terms, forgiving him all his trespasses as he hoped for forgiveness with God. . . ."The General Court referred both petitions to a committee, which on December 22 dismissed Southgate's complaint as groundless.

Possibly the feeling stirred in the community may have caused the Proprietors and Grantees, who managed the affairs of the plantation, to come to regard some of Southgate's bills for surveying as excessive.

(end of page 37)

When some were not paid, Southgate began suing. Barnard McNitt was delegated to make a final settlement with him, and this he accomplished. But Southgate had tired of living in a community where he was at odds with so many, and in 1742 he sold his property and returned to his former home in Leicester. In the first record book of the town of Palmer is the account Barnard rendered to a town meeting, written with the casual informality of a man feeling safe in the good will of his neighbors:

Kingstown, March ye 10th, 1745/6 [1746].

My bill for reckoning with Steward Southgate.Eight Days Service is my Demand but then I give in a Third part and my Demand is Four Pounds old tenor.

And for going to make up with Steward Southgate for his late Sute he Commenced against us, and I made up with him.

And likewise for Going to Boston for a Power to raise our Taxes; and I was Eight Dayes gone, and as near as I can think I have spent Six Pounds in Money and my time, which I count to be at Ten Pounds old tenor [altogether].

And for my assessing two years, Three Pounds old tenor.

And Three Pounds one shilling charge by Southgate this last.

Sum Totle 20:1:00.

"All of the within bill" was voted, the moderator indorsed on the paper. Barnard had no get-rich-quick ideas, with his charge of L1:10:00 a year for acting as assessor.BARNARD McNITT, His Bill.

Mr. Harvey was not happy after his conflict with the Southgate party; in 1744 he spoke to his congregation of leaving, and there was talk of getting a supply for the pulpit, but nothing happened immediately. Perhaps feeling the need of consolation, Mr. Harvey in 1746 made a trip to and from Boston with Mrs. Agnes Little, wife of Thomas Little. According to Temple, "a story got afloat, charging them with unchaste conduct." The parson may have been a weak reed after all.

All the men who had defended him resolutely when he was accused of tippling, thought this a wild oat of another color; they were determined he must go. Two committees were appointed to carry the case to the Presbytery. On June 11, 1747, Barnard McNitt, Seth Shaw, and Andrew Rutherford were appointed to prosecute with the aid of one or more attorneys, and L100 old tenor was voted for their use. Mr. Harvey saved trouble by resigning at the end of 1747. Barnard McNitt made the final settlement, as evidenced by the following:

(end of page 38)

Kingstown, July the 5, 1748.

Recaved from Mr. Barnard McNitt the full of my Reates, Sallery and Wood-reates, during his collection. Ney, the full due to me since my coming to the Elbows, which has been seventeen years past, the Eleventh day of May last, as witness my hand this fifth day of July 1748.

MR. JOHN HARVEY.

Witness preasantThe community then known as Kingstown or The Elbows could not attain a township form of government until the disliked assessment of L500 levied against proprietors' lands in 1733 was paid the provincial government. Time had dragged, with no payment made. In December 1739 the General Court appointed three men -- Colonel William Pynchon of Springfield among them -- to assess the whole sum against the farms of the grantees, and sell the lands of any who failed to pay. Nearly a third of the plantation had been carved off and annexed to the township on the east, now called Warren. That made no difference; landholders of the remaining portion must pay in full.

Samuell Shaw, Juner.

When the settlers petitioned through Samuel Shaw for relief for "this little poor Infant Plantation" from such summary action, the General Court relaxed for a while; then in 1743 demanded L125 at once, and remaining fourths in 1744, 1745, and 1746. Barnard McNitt was appointed at a meeting of Proprietors and Grantees on October 5, 1743 to serve with Samuel Shaw and Isaac Magoon to sell lands of delinquents to enforce payment. It must have been a disagreeable duty. From time to time, when individuals had failed to pay their share, plots of ten to fifteen acres were cut off their farms and sold at auction, until the entire exaction finally was paid.

Hope stirred again that The Elbows plantation might be permitted to have a town government. Barnard McNitt was chosen at a meeting of Proprietors and Grantees on September 22, 1748 to visit Boston to beg the General Court to authorize establishment of a township. He was instructed to "use all due and proper means, with the advice of the members of the Court, as many of them as he can have conference with." Temple relates that "he evidently did some good lobbying, and made a favorable impression." On March 9 following he was sent again to Boston. He submitted the following petition:

To His Excellency William Shirley, Esq.(end of page 39)The petition of the Proprietors & Grantees, so called, in a new Plantation or Settlement commonly known by the name of The Elbows, in the County of Hampshire,

Humbly Sheweth That Your Petitioners have fulfilled the orders of the Great & General Court when the land in said Plantation was granted, fifty families having been brought in and fixt there, & a Minister settled; but recent difficulties arising between the Minister & the People, and there being little prospect of his serviceableness among them, the minister and the people parted, and the people have invited another Minister, who is near settling with them as they hope: But so it is circumstanced with them -- May it please yor Excellency and Honrs, that they are likely to be much embarrassed in proceeding in this affair, as well as divers others, unless they can be erected into a Town, or some way made capable of proceeding regularly & legally to do those things which the interest, peace & good order of so considerable a Number of Families as above fifty make requisite.The Land which yor petitrs pray may be included in this Township corporation, abutts easterly on the Town of Western so called, and westerly on Brimfield, northwesterly on a Plantation called Cold Spring [now Belchertown], northerly on a Tract of Land belonging to the Heirs of John Read, Esq.

And yr Petrs as in duty bound

shall every pray &cIn the name & by order of the Inhabts abovesd,

BARNARD McNITT.

Elbows, May 31, 1749The Governor's Council and the House of Representatives, the two houses of the General Court, voted on June 14, 1749 to grant Barnard's petition and authorize the incorporation of a township with all the rights enjoyed by other towns, including that of electing a member of the House. Governor Shirley refused his consent. The explanation is simple. The British government was dissatisfied with the growing power and independence of spirit of the lower house of the General Court, and wished no additional members elected from newly created towns.

Once more The Elbows plantation tried, when in the autumn of 1751 it sent David Shaw as agent to Boston. He succeeded in getting the colonial government to make The Elbows plantation into a district, with all the rights and privileges of a town except that of sending a representative to the lower house. On January 30, 1752, the General Court passed "An Act for erecting ye Plantation called ye Elbows, into a District by the name of Palmer." The community had to wait until the outbreak of the Revolution to become a town; then an elected representative was welcomed to share in planning for the War for Independence.

David Shaw was clerk of Palmer district until 1755, when Barnard McNitt succeeded, and by annual re-election continued to serve for six years. The second volume of records of the town of Palmer contained many pages of his minutes of town meetings, which I had the privilege

(end of page 40)

of reading in 1917, when J. H. Foley was town clerk. In order to preserve the leaves of the first and second volumes, which contained so much of the early history of Palmer, Mr. Foley had caused them to be enclosed between sheets of thin, transparent silk. At the same time, both volumes had been strongly re-bound.

After Mr. Foley's death the second volume disappeared from the vault in the clerk's office; obviously it had been stolen by or for some antiquarian for its historical value. There is little likelihood of our ever being able to read Barnard's orderly minutes unless the book turns up some day in a library. The handwriting is very much neater than Barnard's rugged script as illustrated by examples shown in adjacent pages. Barnard either had his quill pen on its good behavior, or had employed a younger member of his family to transcribe his minutes for him.

Barnard was elected an elder of the Presbyterian Church on June 4, 1755, with William McClanathan, Samuel Shaw, Jr., and David Spear, Jr. One of his last recorded services as an elder was his participation in an agreement made with the young Rev. Moses Baldwin at Southold, Long Island, to serve as minister at Palmer. On March 3, 1761, it was "voted by the inhabitants of Palmer to give the Rev. Moses Baldwin a call to settle in the work of the Gospel ministry, according to the Presbyterian platform of the Church of Scotland." He was installed on June 17 by the Boston Presbytery.

Then only twenty-nine, Mr. Baldwin had been graduated from Princeton in 1757; in 179 he was honored with a Master of Arts degree. He remained in the ministry at Palmer long after the Ulster Scots who first welcomed him had died; as members of the younger generation moved away to find more fertile soil and better opportunities generally, they were replaced by Congregationalists. When Mr. Baldwin had only a few weeks to go to complete a half century at Palmer, he learned the congregation was tired of a man of seventy-nine. He begged for a younger minister as assistant, and to be made pastor emeritus. He was thrust aside with a pension of $100 a year, and he died two years later. That was the end of Presbyterianism in Palmer, except for a few individuals who may cherish its traditions.

(end of page 41)

1. The person who supplied the information for Alexander McNitt's gravestone gave the wrong age. Alexander was born December 10, 1726 at Worcester, MA. This date appears on page 176 of Vol. XII of the Collections of the Worcester Society of Antiquity, published in 1894. In the record, his name is spelled Alicksander McKnitt and his parents names are given as Barnard and Margritt. Return to chapter text.

2. Barnard's son Alexander was born in late 1726 and he married his second wife in early 1728, so Margaret must have either died in childbirth or sometime in 1727. The only way that Joseph and Arthur could have been children of Barnard's first marriage is if they were born prior to Alexander. This would go against the family tradition of naming the first son Alexander.

Only two sources other than The MacNauchtan Saga list Joseph or Arthur as McNitts. J.H. Temple's History of Palmer, Massachusetts (Springfield, MA: Clark W. Bryan & Co., 1889) lists a Joseph McNitt born in 1727 in Barnard's family (p. 511) and mentions an Arthur McNitt (p. 527), but does not include him in Barnard's family. In a 1764 list of assigned meeting house seats, the book does not make any mention of the two, but Arthur and Joseph McNall appear. Joseph McNall is also mentioned several times as a Revolutionary War soldier. The book Vital Records of Palmer, Massachusetts to 1850 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1905, p 155) shows Arthur as a McNitt in the marriage records, but the Joseph from The MacNauchtan Saga as a McNall. The list of Barnard's heirs in an August 9, 1776, deed selling part of his farm does not mention either of them.

As Joseph and Arthur married in 1761 and 1765, respectively, it would be more likely that they were born in the early 1740's. They are probably sons of the Arthur McNall who died in Palmer in 1744 in his 29th year. The Vital Records of Brimfield, Massachusetts (a town near Palmer) show marriages of Elizabeth McNall in 1761 and Mary McNall in 1754. Perhaps they were part of the same family. The Vital Records of Brookfield, Massachusetts (another town near Palmer) record the birth of Joseph McNall's daughter Polly in 1778. Joseph later settled in Chittenden County, VT and appears in the 1790 census there.

Some other researchers believe that Joseph and Arthur were nephews of Barnard and that their surname was really McNutt, but no records at Palmer use that form of the surname. Apparently a Joseph McNutt died in Nova Scotia in 1785 and an Arthur McNutt died there in 1795.

From the evidence, I do not consider it likely that Joseph and Arthur were part of Barnard's immediate family. Return to chapter text.

3.Barnard married Jean Clark on Feb 19, 1727/28 in Middlesex County, MA. This date appears in Early Massachusetts Marriages Prior to 1800 by Frederic W. Bailey (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1968), Book 3, p. 8. Return to chapter text.

4.These birth dates for Barnard's children are from J.H. Temple's History of the Town of Palmer, Massachusetts (Springfield, MA: Clark W. Bryan & Co., 1889), p. 511. Many of them are identical to the dates given in Vital Records of Palmer, Massachusetts to 1850 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1905), but that source shows Sarah's year of birth as 1736, Mary's as 1741, and Andrew's as 1751. The months and days of birth are the same in both sources for all three. The Vital Records the birth date of Adam as April 16, 1744, which is the same year as in Temple's History but a totally different month and day. Return to chapter text.

Send e-mail